Take d Milk, Nah?'s Jivesh Parasram upends identity play with heartbreaking truths and hilarious asides

By Jivesh Parasram. Directed by Tom Arthur Davis. A Pandemic Theatre and Rumble Theatre coproduction. Presented with Diwali in B.C., in association with Neworld Theatre. At the Vancity Culture Lab on Thursday, October 17. Continues until October 26

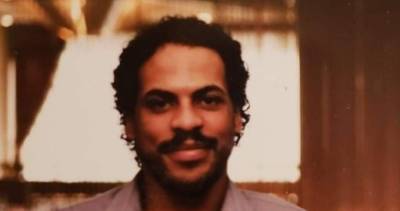

Can a topic as faceted as identity be sufficiently explored on-stage? Does a performer speak directly about his or her own heritage and contemporary beliefs, or speak more philosophically, likening selfhood to a life raft or blade of grass? Jivesh Parasram’s Take d Milk, Nah? is a sojourn into hyphenated history, a one-man show of personal anecdotes and brief history lessons, heartbreaking truths and hilarious asides, all couched in an inventive deconstruction of its dramatic genre.

An Indo-Caribbean Hindu Canadian, Parasram describes the difficulty of existing in the dichotomy of Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, where he grew up: he was either “black” or “white”, with such racial distinctions deepening post–9/11, when systemic ignorance spurred hateful encounters. Tracing a lineage of estrangement, he recounts his great-grandfather’s exodus to Trinidad from India, where famine had been brought on by colonial policies. In reconciling his discrete selves, Parasram draws from a formative episode in his youth, when he was roped into the birthing of a calf.

In a work richly suffused with historical markers and Hindu mythology, Parasram navigates his multiple identities through primers on pivotal elements that informed his thinking, from the scourge of Indian indentured labour to the epic of Samudra Manthan, about an ocean of milk churned by gods and demons. Interleaved with these narratives are humourous feedback on ideology, summed up by Parasram’s mordant impression of Winston Churchill, and a gnomic phrase on belonging, “We are all Jiv,” derived from jivatman, or supreme consciousness.

Eschewing the staid framework of a conformist reflection, the show excels as an interlocked series of moods, shuttling from a laid-back lightness to dazzling exuberance to candid cogency. Set and costume designer Anahita Dehbonehie and lighting designer Rebecca Vandevelde aid in these transitions, with a stout cabinet topped with soil, an incandescent floor yantra, striped curtains of saffron and scarlet, and dramatic lighting on Parasram, clad in a bovine-spotted sherwani, a traditional Indian garment. Completing the setup is the ethereal and urban soundscape, full of the likes of bassy droning and streetcars bustling, and a playlist that ranges from South African jazz and Hindi tunes to the popular sounds of R.E.M., Bob Marley, and Snow.

With his casual, conversational style and inspired audience involvement, Parasram has created a show that doesn’t simply engage at a passive level; rather, it invites an examination of the very genre of the identity play through surprising shifts in its narrative. While the solemnity of the show’s latter moments creates a slight discord with its general levity, it is perhaps a reminder that as with each of us, firm demarcations need not apply.

Comments